So we went to Villa de Leyva, a museum-like town full of white houses and green balconies. For the Virginians out there, Villa de Leyva channels a Middleburg feel. Just replace the English colonial buildings and Arlington/Washingtonian contractor/government worker-types with Spanish colonial buildings and Bogota uppercrust city dwellers looking for a weekend getaway. Lots of Bogotanos have built homes in the mountains around the city and you see more foreigners than almost anywhere else in Colombia, but you also still see your share of campesino grandmothers with nylon stockings, slippers, knee length blue or dark green skirts, a Bavarian-looking hat and ruana (shawl).

Above: The Villa de Leyva main plaza is massive; it becomes a market square on Saturdays, but with the lack of vendor stalls, plaza cafes or decorations of any kind, it looks unproportionally large considering it belongs to a small town. It's like the Tiananmen Square of Colombian plazas (minus long history of violent protests.)

Above: My father and I enthusiastically signed up for this "mild," "beginners" hike through the Villa de Leyva countryside, to the Paso del Angel, a narrow, six foot long strip of mountain with steep drop-offs on both sides. After miraculously finishing the four hour hike, I realized that any aspiration of climbing Mt. Kilamanjaro are years of serious endurance work-outs away. There was a point where it hurt to breath and I wondered if it was possible to have a lung collapse at 25. We were both very thankful that we signed up for the half day hike rather than the full day hike.

For any of you who've been to the Minho Province in northern Portugal, the Villa de Leyva surroundings look/feel a bit like that. Rural, windy, arid, mountainous, home to people with 400 years of history in the area who stay and do the best they can despite a difficult terrain and few opportunities (outside of tourism). I like comparisons to other places. Maybe because I'm never completely happy being in only one place, so I like to imagine I'm somewhere else too.

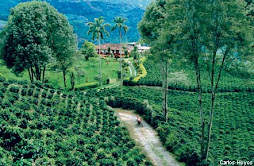

Anyway, unlike much of Colombia, which is vegetated, tropical and almost exploding with color, shades of brown, dull green, yellow and orange characterizes the Villa de Leyva countryside. Tomatoes are one of the only crops that grow successfully here, and long-periods of drought mean the creeks and waterfalls sometimes run dry. But within a 45-minute drive of town, you're suddenly in a humid, green forest with much more fertile land. It's always amazing to me how fast geography changes in Colombia.

Above: Myself, Don Parra and son on our hike. Don Parra is a part-time construction worker, part-time guide and all-around nature expert with two kids and a nice little house a few miles outside Villa de Leyva. Politics: Anti-Chavez, Pro-Uribe, anti-guerilla, pro American basis.

He told us a very sad story about Colombian agriculture, particularly tomatoes. Apparently, planting in greenhouses allows 3-4 harvests in the time normal planting produces one harvest, so all local farmers have now taken on the practice of growing tomatoes this way. It's the only way the banks will give them a loan nowadays. Anyway, in order to grow greenhouse tomatoes, the tomatoes are given a specific chemical mix all day and night and the land they are planted on is left infertile within a few years due to overuse. But there's not really anyone right now to stop the practice. The small and medium tomatoes stay in Colombia; the extra large ones head to Canada and the United States. Apparently, some of these chemicals have gotten in the rivers and creeks, causing mutations among the local people. So far for the theory of third world countries and a simpler, more innocent way of life that doesn't include pesticides or chemicals. It always comes down to supply and demand and from here on out, demand for agricultural goods will probably necessitate these kinds of practices.

In the second picture you can see Leonardo, Don Parra's son, crossing the Cruce del Angel.

Above: My dad enjoying our meal at the Gato Gris in Casa Quintero.

Great post. I'd like to see a photo of the greenhouses. How big are they? Are we talking acres big?

ReplyDeleteNo, they're actually pretty small, surprisingly, and scattered all over the countryside.

ReplyDelete